Algorithms vs Freedom: Is personalisation limiting open-mindedness?

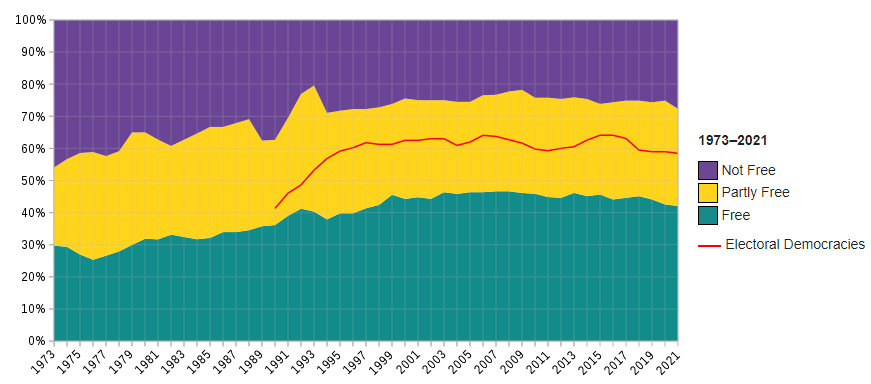

Freedom can be measured in different contexts: economic, political, personal, civil, press, etc. We have seen over the decades that the freedom indexes measured by different organisations have improved but remained unchanged in the past few years.

There are various factors for this stagnation. Personally, I believe the way we, as a society, have been using algorithms in our day-to-day lives is one of the major, indirect contributors. There are many examples to showcase the impact of algorithms in our lives. Generally speaking, I like to classify them into 2 aspects:

1. Polarised consumption:

The information that is passed around in the digital world is not done in a uniform, equitable manner. We hide behind “personalised algorithms” to show and share information, content and thoughts only to like-minded people or with similar interests. Thus, the world today is as polarised as it gets. Things have to be red or blue, black or white, right or left, up or down, etc. There is no more room remaining for the middle ground. This is not limited to social media platforms where political revolutions or conspiracy theories are born and amplified. It extends to the likes of Youtube/ Netflix in the context of the content consumption or even up to the likes of Amazon/ retailers/ brands for their product consumption behaviours.

2. Autonomous conveniences:

Our smartphone keyboards and other smart gadgets have learnt how we type or think and are now able to predict the next words we are about to say. From texting and emailing to composing articles or audio-visual content, there are systems that we are using daily to produce content at our convenience. But, this comes at the expense of our individuality or freedom of thought. If you really think about it, we are training the machine-learning algorithms for the next words or actions that we are about to say or do (including how we drive via Tesla’s autopilot or compose the next globally successful musical track).

From a personalised newsfeed to product customisation, do we really choose the content and product we consume or are the algorithms leading us on what to consume or act on?

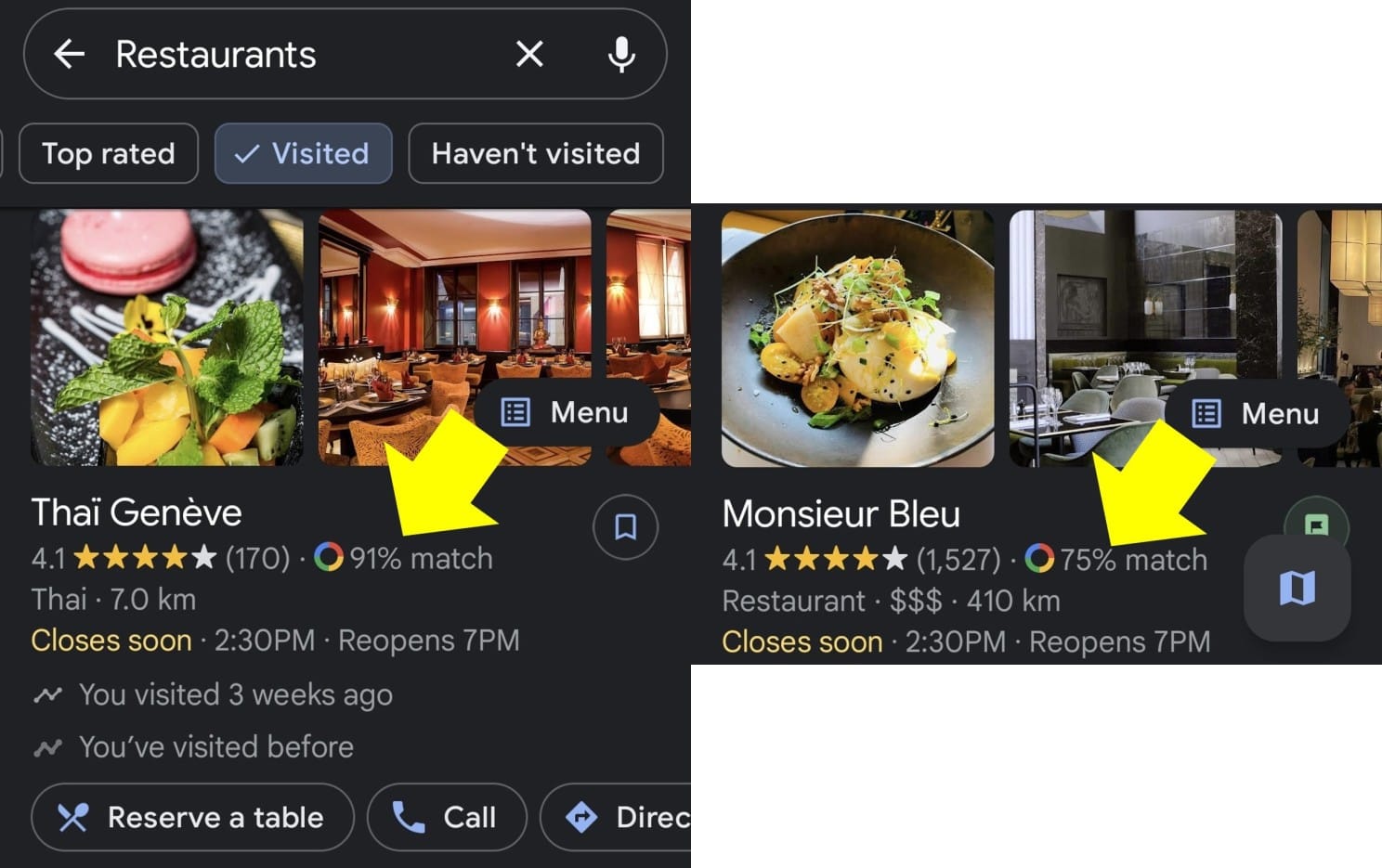

It is not much of a leap from your favourite app recommending restaurants that you will likely dine at with x% certainty to an app that predicts how likely you are about to be involved in a crime (yes, I’m referencing Minority Report’s dystopian future).

Our emotions and how each one deals with them are not binary. Yet, today, we either love or hate the latest streaming show. The opinions in between these extremities are lost in translation for the machines which only ingest data signals from thumps up or down buttons.

So, what can we do about this?

We are starting to see governments and regulatory bodies taking steps to formulate a framework on how, why and when to use algorithms. UNESCO’s recent AI ethics framework is a first step in this direction. China’s policy on limiting algorithms that create addiction is another. But, we need to bring more attention to this topic and have diverse groups of people debating and coming together for the sake of our future.

In addition, we also need companies to deploy ethical AI & algorithm practices. As we see endless possibilities of AI applications in company operations, it will be key to provide training, learning and development around AI and data ethics. These training or L&D programmes must not be limited to IT or data departments but rather they should be company-wide. Lastly, governments and companies must secure and provide strong incentives in their whistleblower policies.

Prevention is better than cure. While we develop a framework to prevent unethical uses of AI, we must also think about the cure when a disaster or a crisis strikes.

I realise that these thoughts that I share in this article might be directly contradictory to my previous articles which explore opportunities of AI in marketing. But, that is exactly the point. We must role-play as our own devil’s advocate and think about our consequences.